Two men rose from beds 1 mile apart on the morning of Friday, May 13, 1898. Both knew death would dominate their day.

J.W. Gazaway awoke at his home on Overhill Street (now Heldman Street) in the Hill District. He dressed and followed his morning routine in a house he shared with his wife, Jerena, and their daughter Jane and two grandchildren. He then stepped out of his house and began a 1-mile journey to Pittsburgh’s Downtown.

Philip Hill emerged from his slumber before dawn in a cell at the Allegheny County Jail. He’d experienced a restless night. Before retiring at 10 o’clock the previous evening, he’d spent several hours reading his Bible. He then slept for a few hours before waking with a start. He called for a deputy sheriff and asked the time — 2 a.m. was the answer. Hill prayed for several minutes, then asked the deputy for a light and smoked a cigar the jail warden had given him. After a while, Hill again drifted off to sleep.

He woke for good at 5:15 a.m. and dressed himself in black pants, a white shirt, black tie and a black jacket — clothes given to him by Sheriff Harvey Lowry. He slipped his feet into leather slippers. Hill he joked that he’d never have to take off his new duds. He drank coffee and ate a breakfast of beefsteak, cake and fruit.

Then he sat and awaited the arrival of his spiritual adviser.

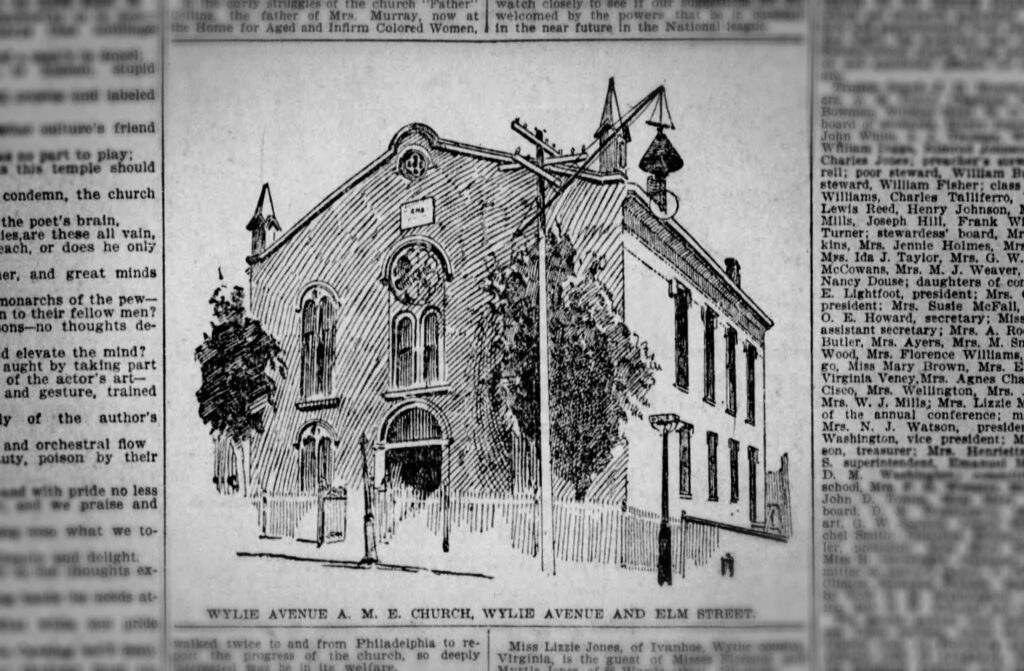

Gazaway made his way through the Hill District streets, perhaps trudging uphill a few blocks to Wylie Avenue and then heading south so he could pass Bethel AME Church, where he served as pastor.

The Bethel building at Wylie’s intersection with Elm was now 50 years old and showing its age. Still, it was a proud two-story structure that housed the city’s oldest Black congregation. From Bethel’s pulpit, Gazaway delivered sermons that addressed the challenges faced by his congregation. He titled one message “The Oppressed Condition of the Negro in the Country and the Source and Means of Deliverance.”

His focus extended beyond Pittsburgh. He knew mobs lynched Black people throughout the American South and in some northern cities. The previous year, Gazaway denounced lynching at a meeting of the AME Ministerial Association. “To hurry an individual without preparation into the eternal condition to which death introduces one is an awful deed,” he said. The fate of souls concerned him.

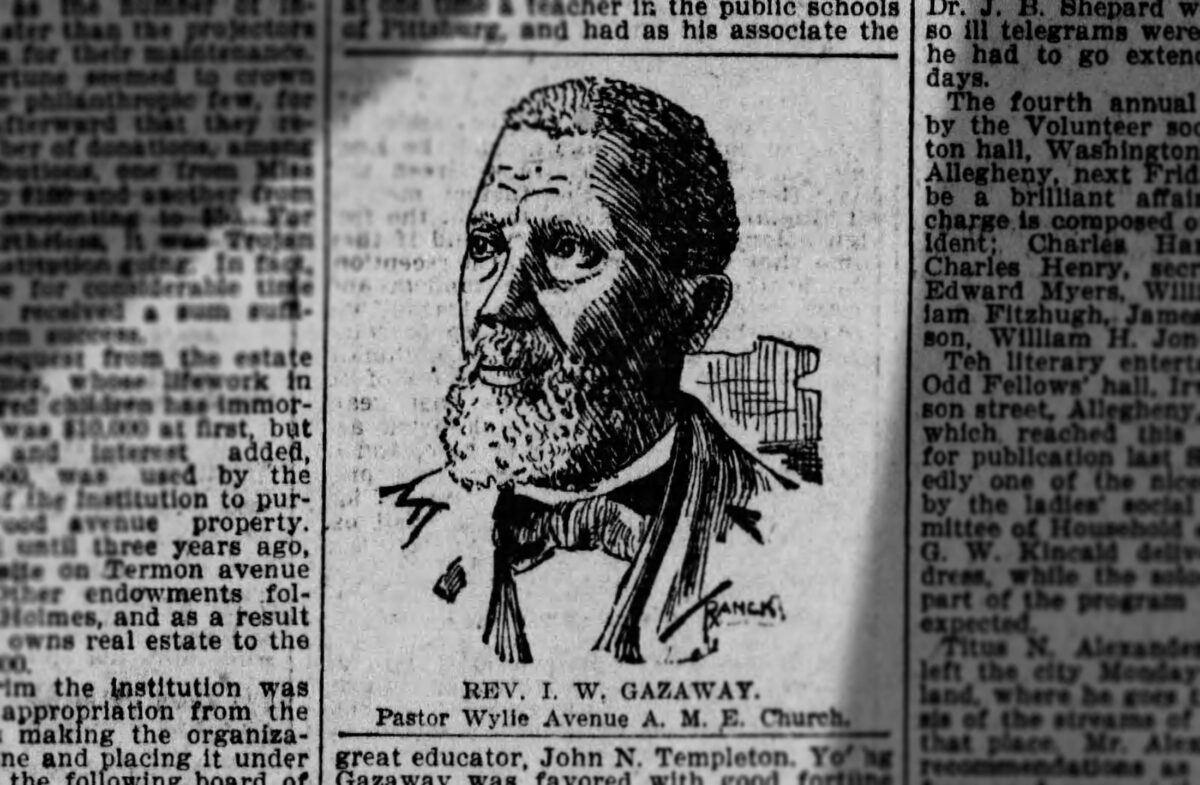

Gazaway, 58, had been a pastor his entire adult life, serving churches in Kentucky and in the Ohio cities of Springfield, Cincinnati and Cleveland. He came to Pittsburgh’s Bethel AME in 1896. His duties included more than preaching, church administration and caring for his flock. On this day, as on many others, his God compelled him to provide a level of grace to a man facing the state’s most brutal act.

Hill, 24, had been in Pittsburgh only a year. He’d come to the city from Virginia to find work. Public records reveal his father’s name — Asa Hill — although his mother is listed as “unknown.” People in Pittsburgh took an interest in Hill when he was charged with murdering a bridge foreman in the nearby borough of Hulton. Hill’s trial began July 12, 1897. The next day, the jury found him guilty. He’d been confined to a jail cell ever since.

Heading down Wylie, Gazaway could look up and see the looming tower of the Allegheny County Courthouse. Gazaway knew something about justice, knew how to wring it out of old institutions bent on bigotry. When he worked as a pastor in Springfield, his daughter attempted to attend a school a short distance from the family’s home. She was refused entry. Only white kids could attend the school. Black children were required to attend a school on the other side of town. Gazaway filed suit against the school board and won.

Most often, though, courts moved quickly to dispatch the cases of Black people, especially Black men. And that’s what brought him now to the imposing stone walls of the county jail, across the street from the courthouse.

Gazaway walked to the Ross Street entrance around 9 o’clock. Jail warden John McAleese greeted the pastor and led him into the jail’s massive rotunda, where five stories of cells seemed something out of medieval times, and up a set of steps to the cell where Hill was waiting.

Gazaway had been visiting Hill for months. The two men had become friends, often reading the Bible and praying together. In fact, Gazaway was now Hill’s only visitor. Hill’s father and stepmother had ceased their visits three weeks ago.

The two men greeted each other warmly, and spent much of the next hour together in Hill’s cell. Gazaway was familiar with these extraordinary moments. The county’s judicial system gave him plenty of opportunities to visit and befriend Black men who’d been quickly convicted — nearly all were tried and found guilty in less than two days.

Months earlier, Gazaway befriended George Douglass, convicted of killing a man after a card game. Douglass and Hill, scheduled to suffer the same fate, were not allowed spend time together, though they did pray for each other.

In Gazaway’s future was William Newman, convicted of killing his girlfriend and so terrified of his fate that he seemed on the verge of collapse. His sentence would so disturb is stepmother that she’d walk to the Smithfield Street Bridge and attempt to leap into the Mononghahela River. Alert pedestrians grabbed her as she climbed the bridge rails. She’d end up in a place newspapers identified as the “insane department of the city farm.”

Then would come Zenus Anderson, whose mother showed up at the jail the day her son’s sentence was to be carried out. At the jail’s Ross Street entrance, she paced back and forth, praying and weeping, then collapsed. “Kind hands bore her away,” according to one newspaper report. A jury had convicted Anderson of killing his wife.

Newspapers reported all the details, and in each story readers saw the name J.W. Gazaway, spiritual adviser and often the prisoners’ only visitor. He sang hymns with the men, served them communion, and prayed with them. When Newman joined Gazaway in singing the hymn, “Jesus, lover of my Soul,” a reporter noted that the men’s strong voices carried to the jail’s lower tiers, where prisoners listened attentively.

Gazaway’s time with Hill ended abruptly at 10:05, when Sheriff Lowry arrived at the cell and announced everything was ready.

“I am ready, too,” Hill said. Then he turned to Gazaway. “You tell my father that he must be a good man and that I want to meet him in heaven.”

A deputy tied Hill’s elbows together tightly behind his back. Then, with Gazaway on one side and the sheriff on the other, Hill walked down the jail corridor to a series of steps. At the entrance to the jail yard, Gazaway fell back and a deputy sheriff took his place in escorting Hill into the daylight.

Once in the yard, Hill could see the scaffolding, which had been assembled and tested the day before. Hill weighed slightly over 200 pounds, and so the rope was adjusted to allow him a drop of four feet so as to break his neck. Hill glanced at the gathered witnesses and medical staff, looking for a familiar face. He saw none.

The lawmen escorted Hill to the scaffolding. There, Hill hurried up the steps. At the platform, he stopped and kicked off his slippers. In his stocking feet, he stepped on the trap door. Witnesses heard Hill praying as the noose was adjusted around his neck. When a black hood was placed over his head, Hill called out, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit, Lord Jesus.”

The moment he finished his plea, the trap opened and Hill’s body dropped. The time was 10:15. His body dangled for seven minutes. Then physicians checked his vital signs and pronounced Hill dead. His body was placed into a simple casket engraved with the words, “At Rest.” By the next morning, the county had received no word from relatives, so officials sent the casket to Highland Cemetery for burial at the county’s expense.

Gazaway returned to his church and congregation at the intersection of Wiley and Elm. Within a few years, he’d be transferred to a North Side congregation. A new church building seating 1,900 people would replace the old structure in 1906 and become a hub of social and culture life in the Hill.

Fifty years later, urban redevelopment would claim both the neighborhood and Bethel AME’s beloved church, which then claimed 3,000 active members. The congregation was forced to move to a new location more than 1½ miles away on Webster Avenue.

Sixty years later, the Bethel congregation is scheduled to receive a level of justice. An agreement with the Pittsburgh Penguins hockey team sets aside 1.5 acres of land in the Lower Hill for the congregation. Bethel’s vision for the parcel includes a restorative justice program, including a $170 million housing program, that will generate revenue for the church

The agreement allows Bethel AME to once again maintain a physical presence in on land its leaders once offered grace to those so easily discarded by others.

Steve is a photojournalist and writer for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, but he is currently on strike and working as a Union Progress co-editor. Reach him at smellon@unionprogress.com.