March 30 marks the birthday of Harper Fair, a forgotten man whose short life reveals much about Pittsburgh’s fragile infrastructures.

Fair was born in 1906 in Fairfield County, South Carolina, deep in the Jim Crow South. Cotton was once king in Fairfield County, but by the time Fair grew into adulthood there wasn’t much work in the cotton fields, so by 1930 he hired on with a construction crew building the world’s largest earthen dam at Lake Murray, near Columbia, S.C.

Once that dam was finished, Fair made his way north, to Pittsburgh. By 1940, he had moved into a boarding house on Miller Street in the Hill District.

Fair departed the house at 7:30 p.m. on Thursday, Nov. 7, 1940, and headed to his job in Stowe, a few miles north of Pittsburgh. There, he joined the overnight shift in the Norwood Tunnel, known today as Stowe Tunnel. His five co-workers were, like those who boarded with him on Miller Street, Southern-born African American men who’d moved north as adults.

One was William Peay, born six years after Fair in Kershaw, S.C. A gold mine in Kershaw once produced more of the soft valuable metal than any mine east of the Mississippi River, but none of the wealth flowed to Black farming families such as the Peays. Like Fair, Peay ended up on a Lake Murray dam construction crew. It’s possible the men met there a decade earlier.

At the Norwood Tunnel, Fair and Peay and their four co-workers climbed scaffolding placed in the bed of a truck about 30 feet from the tunnel’s south entrance and began using chipping hammers to cut away old concrete. It was noisy and cold work in a damp space that leaked rainwater.

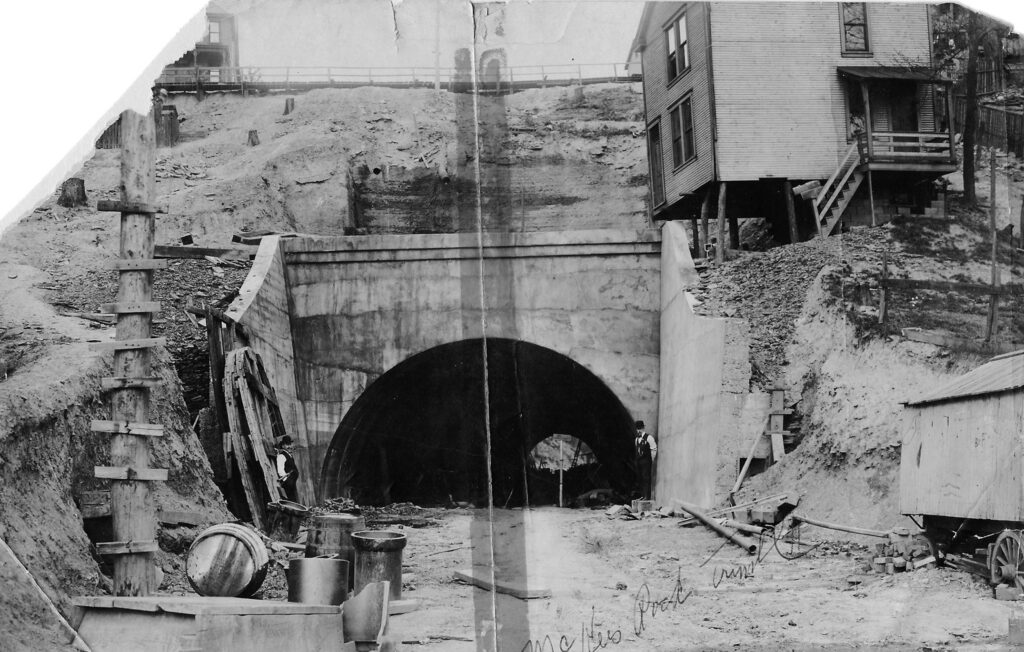

For Stowe officials, the tunnel had been a headache for years. Built in 1909, the 500-foot-long passageway cut through Norwood Hill to connect Stowe’s West Park neighborhood with communities such as Presston and Fleming Park, close to the Ohio River.

The tunnel aged poorly. By 1929, its concrete ceiling crumbled so badly that authorities closed the tunnel to vehicular traffic. A few years later, officials shut off pedestrian access.

That move angered students living north of Norwood Hill. To them, the tunnel provided a valuable shortcut to Stowe Township High School, on the tunnel’s southern end. Without the tunnel, they had to climb several hundred steps over Norwood Hill, a detour that added three-quarters of a mile to the trip and often made them late for class.

Students defied authorities and reopened the tunnel to pedestrians by tearing down barricades blocking the entrances. The move worried Stowe officials. Passing through the tunnel was hazardous. Chunks of concrete fell so often that piles of debris blocked one sidewalk.

Authorities erected stronger barriers in 1938, prompting the frustrated students to strike. Either provide bus service or repair the tunnel, students demanded. Having made their point, the students returned to classes after a week. Tunnel repairs began in 1940. By late fall of that year, the work neared completion.

Shortly after 2 a.m. on Nov. 7, a cracking noise caught the attention of Fair, Peay and their co-workers, stationed near the tunnel’s south end. A chunk of concrete fell from the tunnel ceiling and landed with a thunk on the scaffold. Realizing the danger, Peay bolted for the entrance but didn’t get far. The ceiling crashed down around him.

Foreman James Craig heard the collapse as he walked out of the tunnel’s north entrance. He immediately turned around and saw a cloud of dust where the scaffold had been. Work lights went dark. Craig rushed back into the tunnel.

He neared the pile of debris where Fair, Peay and the others had been working. A voice called out, “Help, get me out.” It was Peay, buried up to his waist. Samuel Hume, who’d been working 20 feet away, heard him too. He and Craig pulled away chunks of concrete and soon freed Peay. Bloodied from head lacerations and suffering a broken neck, Peay walked out of the tunnel, climbed into an automobile and was driven to Ohio Valley Hospital for treatment.

Word of the collapse spread quickly. Soon firemen, police officers and volunteers descended on the scene, grabbed picks and shovels and began digging into the debris pile in hopes of rescuing the five workers who remained buried. The rescuers labored in ankle-deep mud and darkness.

Within moments, they uncovered a body. A large slab of concrete pinned the dead man’s legs, so rescuers left the body where it lay and began digging for others. Massive slabs of concrete stalled progress. A foreman called for a bulldozer, which roared into the tunnel and began biting huge chunks from the pile.

Hundreds of nearby residents, dressed in night clothes, gathered at the tunnel entrance. News photographers arrived and shot flash pictures. Recovering the bodies took time. Dawn arrived as workers carried out the last of five victims.

A few hours later, a police car rumbled into Pittsburgh’s Hill District to deliver tragic news.

Shortly after 8 a.m,. the car stopped at a three-story rooming house on Colwell Street where 36-year-old George Russell lived with his friend Enos McDowell, a laborer on a Works Product Administration road construction crew. Russell and McDowell, both Alabama natives, had been friends for a dozen years. Informed of Russell’s death, McDowell headed to the Allegheny County Morgue to identify his pal’s body.

Two blocks away, on Elm Street, Hattie Cook learned that one of her boarders had been killed. His name: John Wright. The man was something of a mystery, Cook said. When he arrived at her rooming house in 1938 he gave his name as John Wright, “but during his stay in my home he also got mail under the name of Floyd Bynes and also had men and women callers come and ask for Floyd Bynes, and he would answer to that name,” she later wrote in an affidavit.

After learning of the death, Cook dressed and prepared to visit the morgue.

Around 9:30, Louie Turner answered the door of his Rose Street residence to learn of his brother Haywood Turner’s death. He’d last seen his brother about 9:30 the night before, as Haywood was leaving for his first shift on a new job. Louie was the older of the two brothers. He worked at U.S. Steel’s Clairton Works steel mill. Louis arranged for his brother’s body to be returned to his hometown of Birmingham, Ala.

Several blocks west, an officer told Daisy Vann that her common law husband, Charles Rosborough, had been crushed to death. Like Fair, Rosborough, 34, was a native of Fairfield County.

Harper Fair lived in a Miller Street boarding house crowded with other Black workers. He shared a roof with a truck driver, a chauffeur, a bricklayer and several men who worked as laborers on road crews. Steelworker John Crosby, an Alabama native, answered the door when an officer arrived to deliver news of Fair’s death. Crosby identified himself as Fair’s friend and confirmed the identity of Fair’s crushed body at the county morgue. Fair never returned to his South Carolina home. His remains lie in a grave at Greenwood Cemetery in Sharpsburg.

Sources: Allegheny County coroner’s reports, accessed through University of Pittsburgh/Archives Services Center; census reports, death certificates and draft registration cards, accessed through ancestry.com; newspapers.com.

Steve is a photojournalist and writer for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, but he is currently on strike and working as a Union Progress co-editor. Reach him at smellon@unionprogress.com.