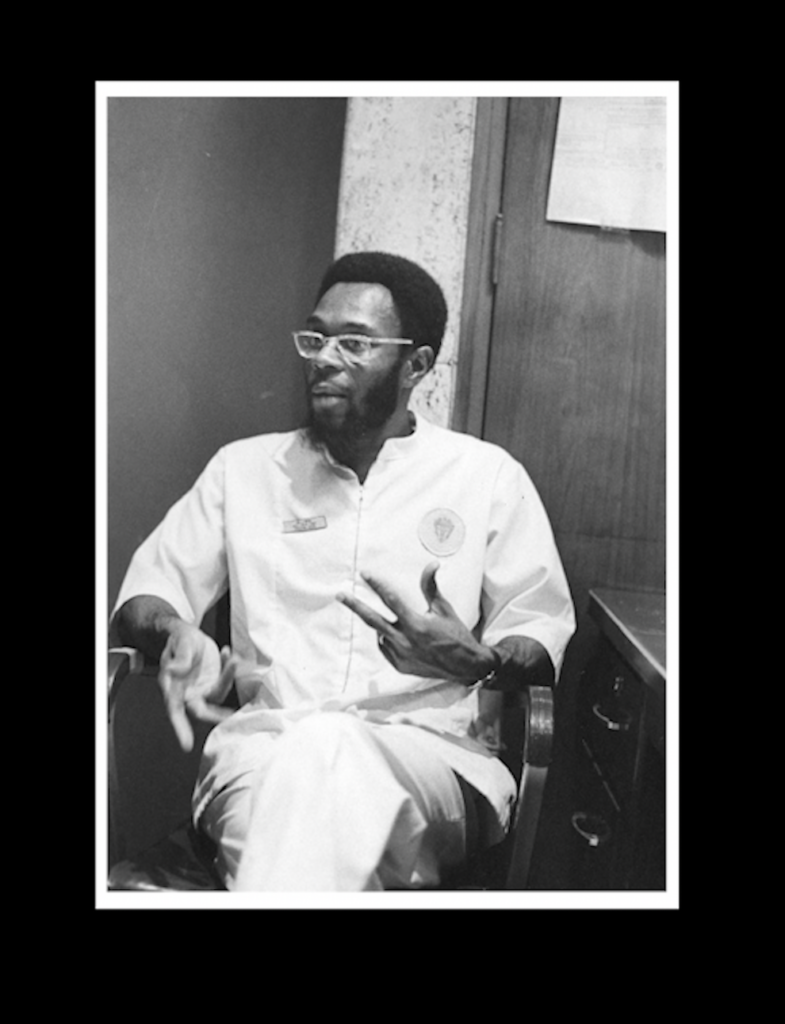

When Pittsburgh EMS Chief Amera Gilchrist and retired Pittsburgh EMS Assistant Chief and former Freedom House Ambulance Service paramedic John Moon take the podium Thursday evening as the city opens its Black History Month celebration, they won’t just deliver speeches.

Moon hired Gilchrist years back and mentored her as she started her career with the city and climbed the management ranks. He couldn’t be prouder of her.

Advocating for the legacy of the Freedom House Ambulance Service — the subject of the city’s 2024 Black History Month exhibit — is Moon’s passion. He said the exhibit that will be unveiled is long overdue and keeps the first professional emergency medical services organization in the country in the forefront, where it belongs.

The exhibit will include photographs, patches, original documentation, doctors’ letters, and emergency medical equipment Freedom House used on its calls during its tenure from 1967 until 1975 when the city stopped funding it and created its own EMS service.

Brandon D’Alimonte, program coordinator from the city’s special events department, said the recognition of Freedom House follows the 2023 WQED-TV documentary as well as Kevin Hazzard’s 2022 book, “American Sirens,” on the trailblazing service. “It seemed like the perfect time to tie it all together,” he said.

Gilchrist and Moon will tell their stories when the exhibit is unveiled at 5:30 that night at the City-County Building’s Grand Lobby, Downtown. Mayor Ed Gainey will also speak.

Phil Hallen, a former ambulance driver who led the Maurice Falk Medical Fund, saw the need for what was then called street medicine. He co-founded the service with James McCoy Jr., a Hill-based entrepreneur who ran a job-training program called Freedom House Enterprises, to ensure that underserved areas of the city had access to it. They reached out to the late Dr. Peter Safar, a University of Pittsburgh anesthesiologist and medical visionary who had developed a method of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and he trained Freedom House medical professionals. The service first answered emergency calls in the Hill District and Oakland and later Downtown. Police answered most of the calls in the rest of the city, merely picking up people and driving them to the hospital without administering medical aid.

“A lot of the men and women who were originally in the Freedom House ambulance service were deemed as unemployable,” D’Alimonte said. “These people were told you don’t count, you don’t matter. They were able to be part of this service, the foundation of modern EMS as we know it.”

Moon provided many of the photographs for the exhibit, D’Alimonte said. Darnella Wilson, who started at Freedom House and moved over to Pittsburgh EMS first as a dispatcher, had a CPR demonstrator and an oxygen rebreather from the service. The University of Pittsburgh Library System contributed, too, so the exhibit and accompanying online materials are a mix of physical medical devices, interviews, photographs and original documentation materials.

The online materials will be released on Thursday, too, and throughout the month via social media posts. D’Alimonte said city staff has interviewed Moon, Wilson and other Freedom House Ambulance Service members, many of whom they found through the documentary producer, Annette Banks. “This was a nice topic — a lot more contemporary — from late ’60s and early ’70s,” he said. “We were able to go right to the source to not only hear their story but interview them as well.”

Moon said the exhibit and online materials “is fulfilling the desires of my heart.” He said it saddens him that many people in the city and throughout the country have not heard about Freedom House Ambulance Service, and that directly relates to when the city dissolved it and started its own service, predominantly led by white people. Although the city had a contract to bring over Freedom House personnel, equipment and vehicles, pledging not to force the trained staff to undergo additional testing or training, that pact was violated, he said.

He traced this to residents of other Pittsburgh neighborhoods not receiving the same level of emergency service and complaining to then Mayor Pete Flaherty. The city cut funding and ordered Freedom House not to use sirens when it answered calls Downtown. “We had to stop at red lights, and it impacted our response time,” said Moon, who worked as a Freedom House paramedic from 1972-75. “You throw all these hurdles and barriers at the organization; it could not be viable in this political environment. [Plus with] the ugliness of racism — you have the recipe for disaster.”

The Freedom House staff entered an environment where they were not wanted. “It made the jobs stressful and difficult,” Moon said. “We were put into a survival of the fittest environment.”

He estimated up to 80% of them left Pittsburgh EMS as a result. Moon persevered and learned he had to be more aggressive and speak up, as he was not allowed to do much on calls other than be an observer. He wrote about his experience for the American Civil Liberties Union last February, including a story about him stepping in to save a man in cardiac arrest when his white colleagues could not.

Moon had to keep quiet about that, but he asked himself, “Am I going to languish or be more aggressive, assertive and outspoken? That is what I decided to do. As I went on more and more calls, I became more assertive — I took the lead. I became the spokesperson for the crew. I wasn’t just cementing my own legacy. I just wanted to survive this onslaught.”

He thrived, although it wasn’t easy. Moon said the city went 10 years without hiring another Black professional. He voiced his concerns as he worked to receive promotions where he could make a difference. Management asked him to create a diversity program. He used the Freedom House Ambulance Service model, reaching out to the minority community, training people in emergency medicine and hiring them.

That is where and how he met Gilchrist. “She is my crowning glory. I am very, very proud of her accomplishments,” Moon said. “I mentored her through her career.”

He posted about her on LinkedIn in 2015: “One of the best Black females to ever wear the Pittsburgh EMS Uniform, a consummate professional in every aspect of the word. Energetic and smart, hopefully will someday lead the department.”

After he retired from Pittsburgh EMS in 2009, in addition to starting a home health care business with his daughter — he has retired from that as well — Moon traveled the region and across the country telling the Freedom House Ambulance Service story.

It pained him that the service’s achievements had become a footnote in emergency medical service training and history. One of Freedom House’s medical directors, Dr. Nancy Caroline, who developed the textbook “Emergency Care in the Streets,” is recognized as the “Mother of Paramedics.” But Moon found that in a recent edition of her book, Freedom House was relegated to a footnote, its contributions more or less removed.

Further, most EMS systems had never heard of it, he said. But now it has a lot of momentum, thanks to the WQED documentary, which won an Emmy and is recognized by PBS as a major production and shown throughout the country, and Hazzard’s book.

He addressed the National Association of Emergency Physicians conference in Austin, Texas, this month as the keynote speaker. The more than 1,500 professionals there heard him talk about “The Legacy of Freedom House Ambulance Service: The Black Men Who Became America’s First Paramedics.”

At 75, he wants the Freedom House Ambulance Service to get recognition in its home, too. “I still want this historical perspective out there. … I am totally committed to it,” Moon said.

The city has some public remembrances of the service, including the plaque on the Hill District Federal Credit Union on Centre Avenue, which was the headquarters of Jim McCoy’s Freedom House Enterprises; another on the site of UPMC Presbyterian, where the Freedom House ambulance service operated but the original building is gone; and a Heinz History Center Freedom House display, which is part of its permanent exhibit “Pittsburgh: A Tradition of Innovation,” as reported by WESA’s Bill O’Driscoll in 2022. Moon also wants the Freedom House logo back on city ambulances, something he pushed for 20 years ago and will revisit as many of those vehicles have been replaced.

Moon’s heart’s desire, he said, is having the Freedom House Hill District building designated a historic building site. “I have to reach out to the right people who can get it done. There’s a lot of redevelopment going on in the Hill right now. Maybe the time is right to have that topic brought to the masses for discussion.”

The retired EMS assistant chief said every time he sees an emergency vehicle he looks at the people inside. Moon wants to see if there is someone “who looks like me” and wonders if the people inside understand where the EMS system came from. “And unfortunately, many times the answer is no,” he said.

Because of that, Moon will still push for recognition nationally. “One of the things that is keeping me going on this project is that I want the history of EMS written in every paramedic training program, every EMT training program, every EMS physicians training program,” he said. “And if I have my way, Freedom House’s logo would be on every EMS vehicle in this country. Without Freedom House that overcame the barriers and obstacles and disappointments, we wouldn’t have this modern EMS system. That’s what keeps me going.”

Helen is a copy editor at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, but she's currently on strike. Contact her at hfallon@unionprogress.com.