On the morning of Independence Day 1849, people from as far away as Pittsburgh began gathering in a grove at the Ohio-Pennsylvania state line just east of East Palestine, Ohio. It was, according to newspaper reports, “a beautiful day” for a celebration, and within a few hours the number of attendees had swelled to an estimated 4,000. Hundreds dined at tables set up for the occasion. An American flag, hoisted high on a pole, blew in the breeze.

The crowd must have astonished the residents of East Palestine, then a tiny farm community known simply as Palestine. In 1840, one local historian noted, the village was home to 88 souls, three sawmills, three grist mills, two stores, a hotel and a one-room schoolhouse. Residents who wandered over to the grove heard windy speeches promising something new for the town: a railroad.

Trains would transform the area, proclaimed the day’s keynote speaker, Solomon W. Roberts, chief engineer of the Ohio and Pennsylvania Rail-Road Co. Newly formed, the Ohio and Pennsylvania’s mission was, at the time, a bold one: connecting the two states by rail.

Trains would benefit industrialists, of course, by linking the manufacturing centers of Pittsburgh and Philadelphia with Ohio’s cities (Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati). But the rail company gave assurances that Ohio’s farmers would benefit, too. Railroads offered fast and relatively inexpensive access to urban centers in need of food.

After the speeches, dignitaries at the July 4 ceremony shoved Pittsburgh-made spades into the earth, breaking ground for the new “iron river” — promising prosperity and growth.

And indeed, the rail line did open up markets for produce local farmers raised — and for the coal beneath their properties. Later, the railroad brought industry to town. East Palestine factories cranked out pottery and rubber products. The town’s population grew from 2,500 in 1900 to 5,700 in 1920.

As they have done in small towns throughout Ohio and Pennsylvania, trains also delivered occasions of terrific destruction and tragic death, and more than a century before the toxic train derailment of 2023, one moment in which the small town drew national attention.

A mournful return

Shortly after 9 o’clock on the overcast morning of Sept. 18, 1901, a westbound steam locomotive draped in black mourning cloth and pulling eight Pullman cars chugged past a crowd of residents standing on an East Palestine hillside. Men removed their hats. Women waved handkerchiefs. Boys stood tense, waiting for the train to pass so they could fetch their prizes.

The train had departed the nation’s capital the night before, traveling in the darkness through small towns in Maryland and Pennsylvania, past bonfires lit by those trying to keep warm and awake as they waited to pay their respects. Shortly after sunrise the train passed through Pitcairn, where factory girls clutching their lunch pails paused to watch. Church bells tolled in Braddock as the cars passed. Mill workers ceased their labor.

In Pittsburgh, the train lumbered across the Allegheny River on a bridge lined with men and boys standing so close to the track that their coats almost touched the passing cars. Boatmen blew mournful blasts from their horns as the train headed north on tracks following the Ohio River.

It was at East Palestine, news reporters noted, that President William McKinley, dead from gangrene caused by an assassin’s bullets, crossed the state line and made a final return to Ohio, the state of his birth. The train would later screech to a stop in Canton, where McKinley’s casket would be buried.

At the time, East Palestine was “a little village nestled between two great hills,” according to one McKinley biographer. A picture shot from the last train and later published in Harper’s Weekly shows a cluster of people standing on the hillside. The train was pulling away, and already several people were clamoring down to the tracks to collect coins they’d earlier placed on the rails. Smashed and bent, those coins would be treasured as keepsakes.

Death at North Market Street

Wilda Nulf and Edith Kissinger spent the night of Saturday, Feb. 1, 1954, bowling in a women’s league at a place called the Ranch on Route 14, a few miles north of East Palestine. Afterward, the two friends stopped to grab a late-night bite at Brown’s restaurant. About 2:15 a.m., they climbed into Nulf’s 1953 Buick sedan and headed home, driving south past the now closed and darkened storefronts in downtown East Palestine.

Watchman John Ianni, on duty at the North Market Street railroad crossing, saw the vehicle coming his way. A fast-moving 15-car passenger train was approaching from the east. Ianni lowered the crossing gate and rang a warning bell. Crossing lights flashed.

Nulf apparently did not see or hear the warnings before it was too late. She drove through the wooden gates and smashed into the fourth Pullman car, named the Andrew Carnegie, as it sped by. The impact ripped apart Nulf’s sedan, scattering pieces 200 feet along the track. A portion of the car’s motor crashed through the window of a store just north of the crossing. A chunk of the wreckage slammed into the side of the same building, creating a gaping hole.

Nulf, 36, a mother of three children, and Kissinger, 35, mother of two, were both killed instantly. Their bodies were found lying under parked cars 60 feet west of the crossing. Officials stressed that the bodies were not mutilated.

Newspapers noted that a similar accident occurred Sunday morning, April 28, 1935, when four young men returning from a dance ignored warning bells and drove their vehicle through a lowered gate at the same intersection. A westbound locomotive struck the automobile near its left rear wheel, hurling it against an iron fence. The force of the crash threw the four men from the vehicle. They landed on a station platform 30 feet away. All four died.

Three were brothers — Carl Renner, 24, Omar Renner, 22, and William Renner, 20. All were mechanics who’d recently arranged to open a car repair shop in Enon Valley, Pennsylvania. The fourth victim was Jesse Walker, 24. All lived in Enon Valley.

Days of calamity

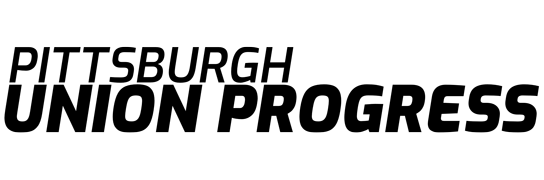

A series of grinding and crashing noises jolted residents along West Clark Street from their sleep around 2 a.m. on Saturday, Aug. 26, 1961. Some quickly rose from bed and, bleary eyed, peered out their windows in time to see jets of fire shooting from under rail cars skidding off the nearby tracks. Those residents may have uttered a few curses of frustration and anger. East Palestine was in the throes of a two-week span in which rail calamities would bedevil the town.

On this morning, 38 cars and five diesel engines on a westbound train derailed and piled up near the Royal China pottery plant. Two cars punched a hole in a wall at the factory. Workers scurried for cover. None was hurt. Five crew members on the diesel engines were shaken but not seriously injured. The wreck tore up hundreds of feet of track. Investigators blamed an open switch.

Within a few hours, crews arrived to clean up the wreckage. A few local bulldozer operators joined in to speed up the process. By Saturday afternoon, several hundred spectators had arrived, and the scene “took on the air of a county fair,” reported the East Palestine Daily Leader. Large steam cranes lifted the damaged cars. It was quite a sight, but it felt like a rerun.

Crews had only recently cleared up the wreckage left by a crash six days earlier, when 19 cars on an eastbound train traveling 40 to 50 miles an hour hurtled off the rails near the same location. That crash, which occurred around 11:15 on Sunday night, Aug. 20, damaged several hundred feet of track. Most of the derailed cars were filled with limestone bound for steel mills in the West Virginia cities of Wheeling and Weirton; a number of those cars spilled their loads near the tracks.

East Palestine’s residents and officials looked at the scene and counted their blessings. Had the derailment occurred east of the North Market Street crossing, the cars might have struck one of the gas stations situated there.

The cause of this incident? Officials said a burned-out bearing sheared off an axle on one of the cars.

Rail demons weren’t finished wreaking havoc on the town. Around 10:30 on Saturday night, Sept. 1, 12 cars derailed, once again near the pottery plant. In fact, some of the cars piled onto wreckage left from the crash a week earlier. A fire siren sounded. Hundreds of people rushed to the scene. One of the derailed cars, a tanker, was believed to contain highly volatile industrial alcohol, so local firefighters stood by until someone checked to see the car was empty.

‘Destruction — Penn Central Railroad Style‘

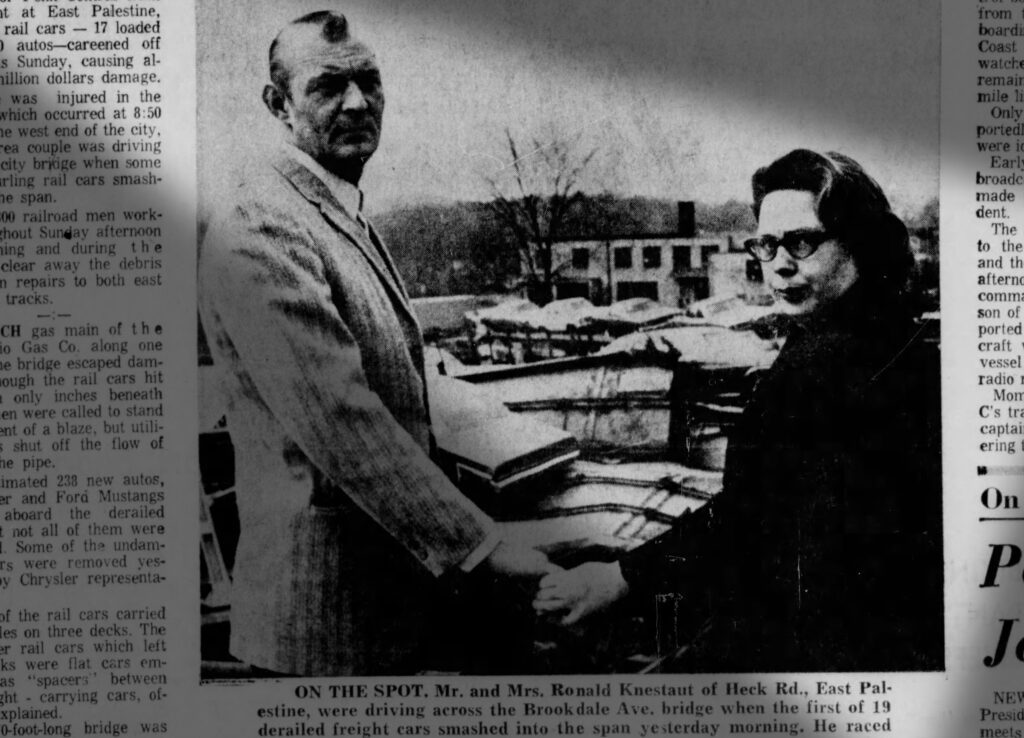

While driving his 1965 Buick south over the Brookdale Avenue Bridge on the west side of East Palestine early on the morning of Sunday, March 1, 1970, Ronald Knestaut looked over at the train barreling along the Penn Central tracks 30 feet below and noticed something odd. The cars were leaning. An instant later, a loud crashing noise jarred Knestaut and his wife, Lilly. Sitting in the passenger seat, Lilly looked out the window and saw chunks of twisted metal rise above the side of the bridge. Ronald felt the back of his vehicle drop as the roadway began to collapse. He smashed the gas pedal and sped across the bridge as the 70-foot span buckled with a roar.

On the tracks below, several rail cars carrying new automobiles hurtled off the track and overturned. Smashed freight cars and crushed automobiles jammed into the space under the bridge, preventing the span from collapsing completely.

Thus ended the Knestauts’ leisurely trip to a local restaurant for breakfast.

Seventeen of the 19 derailed cars were hauling automobiles fresh off the assembly lines. Those vehicles lay scattered in all directions, some overturned. Damaged freight cars lay on their sides in a zigzag pattern.

News of the crash spread quickly through town. Hundreds of spectators lined both sides of the tracks. Some got close enough to touch the wrecked automobiles. By afternoon, the crowd had swelled to thousands. People watched as wrecking crews and firefighters cleaned up the mess and salvaged what they could.

Penn-Central officials arrived after a few hours. One newspaper reported they were alleging the bridge had caused the disaster by collapsing on the train. Company detectives swarmed over the area, asking residents what they’d seen or heard. One woman ordered the railroad officials from her home.

The next day, the East Palestine Daily Leader published several photos of the crash site with the headline “Destruction — Penn Central Railroad Style.” An investigation soon determined the cause: A wheel truck fell off one freight car, which toppled off the track, taking 18 others with it.

Penn Central officials promised to replace the bridge, but the company went bankrupt before doing so.

Death on an Amtrak train

Three years after the Brookdale Avenue Bridge crash, a westbound Amtrak passenger train called the Broadway Limited roared through town at 60 miles an hour during a heavy wind and snow storm. It was just past 3 a.m. on Sunday, March 18, 1973.

Engineer L.P. Moffett saw a “kink” in the track east of the North Market Street crossing and tried unsuccessfully to stop the 19-car train. Four cars skipped off the track and rolled over, tearing out several poles carrying railroad communications wires and crashing through a wall of a tank fabrication plant.

George Wintoniak, 53, a division engineer for the railroad company and a World War II veteran, died of head injuries sustained in the crash. He was from Haverford, Pennsylvania, and was riding on a pass to Chicago. He left behind a wife and a daughter.

Twenty injured passengers were transported to a hospital in Salem. All but a few were treated and released. Most of the remaining 167 passengers crowded into an East Palestine fire station, where they were served coffee and doughnuts. They later boarded another westbound train at the North Street crossing.

Officials said the derailment was caused by a misalignment of the tracks due to a previous train separation. The Youngstown Vindicator newspaper reported it as East Palestine’s fifth train wreck in 10 years. East Palestine officials and residents were miffed.

The chair of the town council’s safety committee, Byron D. Cope, telephoned Ohio Gov. John Gilligan to complain about the Penn Central rail company. Cope reminded the governor that a 1970 crash destroyed the Brookdale Avenue Bridge, which continued to await repairs. On least three other occasions, homes and businesses had been damaged by flying debris from passing trains.

The Public Utilities Commission of Ohio needed to step up, East Palestine leaders said. They alleged Penn Central ignored speed limits and failed to maintain roadbeds and rail cars. The PUC had earlier ruled the railroad company was responsible for replacing the Brookdale Avenue Bridge, but nothing had been done.

“I feel it is time we go all out in our fight against the situation,” said local safety committee member E.C. Rhodes.

The next year, exasperated East Palestine council members agreed to spend $75,000 to build a new bridge at Brookdale Avenue, with the county picking up $50,000 of the cost.

Enough is enough

Mary Mansell was baking pies at Mackall’s restaurant on East Taggart Street shortly after 7:13 a.m. on Thursday, May 13, 1976, when bricks and other debris came crashing through a kitchen window. Much of the debris came from the Bulldog Amoco service station next door, which had just been pummeled by a Conrail boxcar, loaded with lumber, that had jumped off the tracks near the Pittsburgh Chair Co. The car continued to travel along the tracks to the North Market Street crossing and then swung sideways, smashing into a wall of the Amoco station.

Dave Kissinger, son of service station owner William Kissinger, was in the rear of the building at the time, but he fled to safety and was unhurt. The elder Kissinger was reaching the end of his rope. His business had been damaged a number of times by junk flying off of passing trains. Now a train had demolished the south wall of his business. Maybe, he said, he’d just close.

This story is part of collaborative coverage of East Palestine between the Pittsburgh Union Progress and the New Castle News, funded in part by a grant from the Pittsburgh Media Partnership.

Steve is a photojournalist and writer for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, but he is currently on strike and working as a Union Progress co-editor. Reach him at smellon@unionprogress.com.